Episode: 13

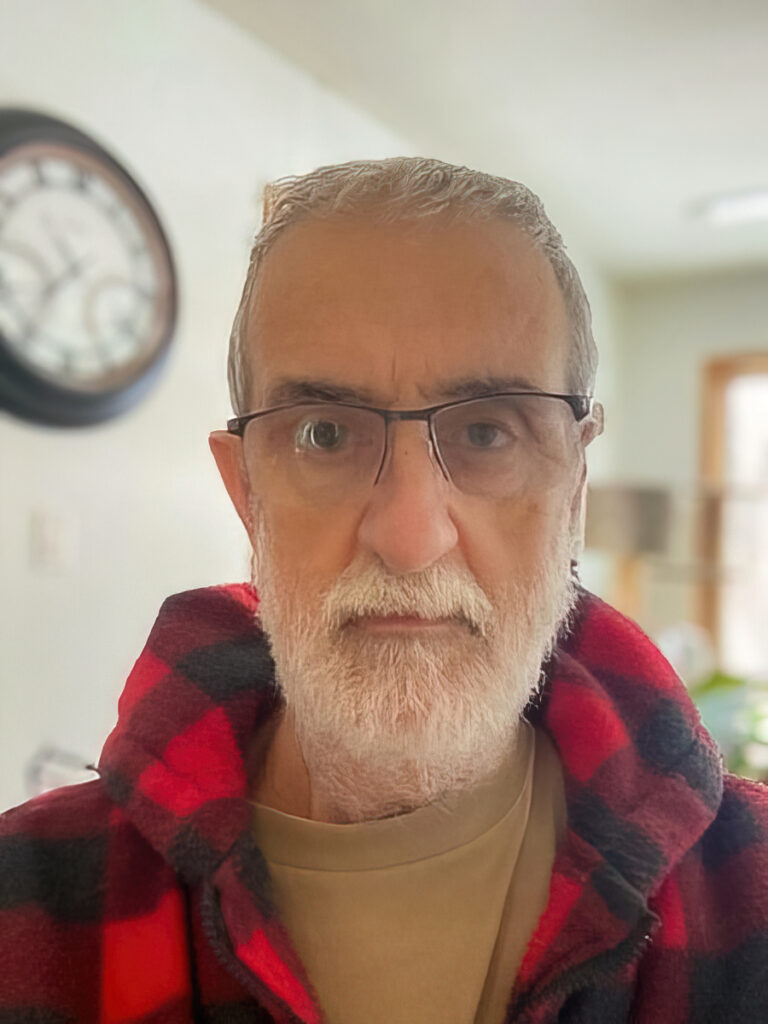

Francois Labelle

In this week’s episode of The Extensionists, Jay Whetter and Toban Dyck chat with the farmer and retired Manitoba Pulse & Soybean Growers executive director about everything from his work travels around the world to his Hollywood famous mini donkeys.

Listen here:

Transcript

Episode 13 – Francois Labelle

Tue, Mar 18, 2025 10:01AM • 1:06:44

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

Agriculture, pulse crops, lentils, peas, Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers, extension, on-farm research, market development, consumer interaction, donkeys, miniature donkeys, crop rotation, export markets, disease management, agricultural innovation.

SPEAKERS

Francois Labelle, Toban Dyck, Jay Whetter

Toban Dyck 00:03

This is the extensionist conversations with great thinkers in agriculture. I’m Toban Dyck and I’m Jay wetter. Hey, Toban, how you doing good? How are you Jay? So, Jay, what’s the right into it? Yeah, okay. Right into it, yeah. What is the craziest thing you’ve ever eaten? Well,

Jay Whetter 00:24

I was in China and I had chicken feet, which isn’t I’m gonna get to the more crazy one, but you can have chicken feet at dim some places here. But I was bound and determined to eat some sort of insect. I just thought, I need to try these. And so I said to this guy, Jackie, who is helping us in China. I was there for a canola Council tour, and I said, Jackie, I want to try some sort of insect dish. And so he found this, these mealworms. Like it was a bag of mealworms. And he said, as my parting gift from him, it was this, this bag. And so I took it back to Canada and tried some. I think that’s the strangest thing I’ve eaten. I’ve also eaten the crickets, the prairie cricket clusters from from here, the chocolate clusters, but they taste more like chocolate than than crickets, Prairie cricket farms.

Toban Dyck 01:20

And yeah, I’ve heard of them. No, I haven’t never had them. What’s the serious

Jay Whetter 01:23

thing you’ve ever eaten? Yeah, it’s

Toban Dyck 01:27

similar. Actually, it was in, it was in Korea, Jamie and I, my wife and I were teaching English there, and it was worms. It was a worms. It was like, but similar representation was in a bag, and it was, like, deep fried. I think it was, I think they were silk worms. Okay, that was, that was pretty wild. I mean, so I like, crazy. When you say crazy, when I say crazy, I like, a flag went up. Like, it’s like, you know, yeah, how we use that for from what we would, that’s right. So I want to preface that, what do they get isn’t objectively crazy, because these, you know, lots of things that I would, I would eat, are would be considered crazy for others, but

Jay Whetter 02:05

it’s, yeah, and insects are probably fairly sustainable protein source.

Toban Dyck 02:13

Really? Why not? Yeah. I mean, the kinds of proteins we eat, I think, I think it’s very fascinating topic, like Anthony Bourdain, did you? Did you love that guy? Yeah, you watched a lot of his shows, yeah, so I haven’t yet watched the one. Didn’t he have a whole show premised on him traveling around the world and eating things well, like eating kind of strange things. Well, I

Jay Whetter 02:37

remember the, I mean, the This doesn’t seem strange now, but when I saw him do it the marrow bones, which now you can kind of right, tipping the marrow out, out of the bone into your mouth. Yeah, you remember, did you ever watch Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom when they said they eat the mike? You brain, yes. And then they eat like lots of bugs. I just remember the vision of this guy eating like a huge beetle and kind of just scraping it off his into his mouth, like, you’d like, one of those artichoke leaves, you know, it kind of just scraped the Oh yeah, flesh off, and then you have this hard, fibrous leaf left over. It’s like eating the bugs. I’m

Toban Dyck 03:16

very, I’m very texture sensitive when it comes to food, like, you know what it is doesn’t really matter, but it’s like, it’s, it’s the mouth feel, it’s, I do not want to say that you

Jay Whetter 03:32

just cringe when I said that I did cringe. Like, cringe. Yes, some people don’t like the word moist, like, so like, like, 99%

Toban Dyck 03:41

of the people I know don’t like the word voiced

Jay Whetter 03:46

mouth feel okay, so we shouldn’t have said that. Well,

Toban Dyck 03:49

we could have okay. We were glad we did. You know, you got to get it out there.

Jay Whetter 03:55

Okay. Well, we’re going to talk with Francois Labelle today, and I hope at some point we get to ask him about his brain balls that he ate while he was in Italy. I

Toban Dyck 04:06

have no doubt that we’ll get there with Francois. Yeah, he’s an old he’s an old friend and and I’m looking forward to this chat. All

Jay Whetter 04:14

right, on to Francois LaBelle, who is a former executive director with the Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers. He’s also done many things in in Manitoba Agriculture, and he has interest in small donkeys, among other miniature miniature donkey nature. So that’s the difference between small and miniature. This is this is a questionable reserve for Francois

Toban Dyck 04:35

Hunter friend. But before we start today’s interview, we want to thank our episode sponsor, Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers.

Jay Whetter 04:47

Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers is proud to support the pulse root rot network. It

Toban Dyck 04:52

is a collaborative approach to root rot research and management for peas and lentils in Western Canada. The website

Jay Whetter 04:58

provides agronomy recommend. Information on breeding efforts and background information on pathology to help increase your knowledge of the root rot diseases that could affect your farm’s bottom line, visit

Toban Dyck 05:09

root rot.ca to find out more.

Jay Whetter 05:18

All right, our guest today is Francois LaBelle, and Francois is a long time Manitoban, involved in various parts of the agriculture industry here, including, I don’t know, 20 plus years as a merchant with Continental Grain, then agricore, Executive Director for the Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers, and involved in all sorts of other things, including a number of boards, and also has 60 or so miniature donkeys. Do you want to start with

Francois Labelle 05:48

the donkeys? Well, we could start with the donkeys, if you like.

Jay Whetter 05:51

Show me some pictures. They’re very cute. Why 60? What? Why not just one? Isn’t one enough?

Francois Labelle 06:00

Is one peanut enough

06:04

peanut donkeys, yeah, potato chips.

Francois Labelle 06:06

You can never only have one beer. And truly, donkeys should always be at least in a pair, because they are very bonding animals and very social animals, and they prefer their own kind. Okay, so you should never only have 112,

Jay Whetter 06:24

or 60, those are your three choices, not one, two or six.

Toban Dyck 06:28

So full disclosure, though, like Francois, it’s funny. I mean, watching you do the intro the whole time, I’m like, I should really interrupt you, yeah, because what did you want to say? Well, like, nothing, nothing in particular. But just like Francois and I have known each other for a long time. In fact, Francois hired, hired me, and he was, like, my my introduction into kind of the egg like egg sector, like working, working in the industry. So my first job was communications with Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers, and Francois was my boss. Oh, right. So Tim and I have known each other for, this is going, that’s pretty close to 10 years, actually. Now, yeah, it would, I can’t, yeah. I mean 20, I think 2016 is when, is when I started in MP, SG, yeah, that’s, yeah, that’s, that’s around the ground, the corner of 10 years. So, okay,

Jay Whetter 07:16

enough about that jazz. Let’s get back to the

Toban Dyck 07:20

donkeys. Full disclosure. So what I know of Franco’s donkeys is, is a I’ve been to his farm numerous times. I’ve taken nieces and nephews. I’ve taken friends, and every time, it’s a huge hit. They are incredibly cute. They’re amazing creatures. But when we should get friends who had to talk about this, not just you and I, because it’s, you know, he’s here with us today. They’ve been in a movie. They’ve been in a Hollywood film. A Dog’s Purpose. I think it’s called,

Jay Whetter 07:56

that’s correct, yes, what did your donkeys do in the movie? Did they have speaking parts. No,

Francois Labelle 08:01

they, they just had to, just had to be a donkey, you know, they, they, they were referred to as horse dogs, because donkeys are very, very much like dogs, when you get down to it, and they’re very, you know, they could, they’re they’re affectionate, and that type of thing. And in the movie, one of the first generations of of the dog ran across a baby donkey. Okay? And the after the fifth generation, the old dog ended up back on the same farm where we started. We started with the baby, and we had the old donkey. And yes, the old donkey met the baby, Don or met the dog, and a different generation, different kind of dog, but it

Jay Whetter 08:53

okay. So it started. The movie included your your bait, one of your baby donkeys. That’s one of your mature donkeys. But from the in the movie plot, it was the same donkey, yes, yeah, yeah, that’s good. Okay, so the dog, the dog in the Dog’s Purpose, knew Yes, donkey, the donkey was new,

Francois Labelle 09:10

knew the donkey and the donkey, the the old donkey was was interesting because it would prance back and forth. You know, when the dog came close, it would prance back and forth. And the ironic thing is that dog, that donkey’s name, was Prancer. Oh, perfect, and we still have her today. Oh yeah, so we’re not going to

Jay Whetter 09:30

talk all about donkeys, but can you just tell me why you got into donkeys? What was it about?

Francois Labelle 09:36

Actually, back years, a few years before, back in 86 when I first bought a farm, we were growing strawberries, and the strawberry industry was evolving and so on. I always say that people like my mother, that used to pick 25 pails of berries a day and make jam for the family and go back a few days later and do it again. Those. People passed on. So the market got more difficult. So we developed. We started a small, you know, petting zoo, family farm that people can visit. We had chickens and ducks and geese and horses and sheep, and one day, went to buy some sheep from fella, and he had a donkey. And I always wanted a donkey, so we brought a donkey home, and like I said, you can’t only have one. So it evolved. And we we increased our donkeys, and then we got into purebred animals, and we showed donkeys. And just

Jay Whetter 10:35

when did the miniatures become part of your life?

Francois Labelle 10:38

The original one we bought was, was actually a miniature. And

Jay Whetter 10:41

what, what makes a donkey a miniature? A miniature is

Francois Labelle 10:45

got to be less than 36 inches at the withers. And anything higher than that would be a small standard, and then a standard and a mammoth. And

Toban Dyck 10:54

just for our lay audience, the withers is basically

Francois Labelle 10:58

at the shoulders, at the top of the shoulders.

Toban Dyck 11:01

Interesting, very, very, very interesting. So Francois. But when I think about talking to you, with you on a podcast, I think about stories, so many stories, and so many great stories. When you think back and your career in agriculture, which I know isn’t, isn’t over, you’re still, you know, you’re still involved, and you’re still well read, which we want to get to. But what are some of those? What are some of those kind of benchmark stories and moments that just,

Francois Labelle 11:38

you’re making it difficult, that’s good,

Toban Dyck 11:41

not the hot seat. I just thinking about, I mean, I can recall some of the, you know, like you think you were telling me once about this wild meal that was that was prepared on your on your farm, like a big pig roast and helicopters. Maybe, maybe I’m getting things mixed up with like

Francois Labelle 12:02

a movie. No, it was. We used to, we used to hold a far a fall barbecue. When I worked with Continental Grain, we’d held a fall barbecue where we’d actually put upwards of four or five barons of beef in the ground, cook them overnight, you know, for a 12 to 14 hours type thing, and and then fed a number of people. And, you know, anywhere from 100 to 150 people. And we didn’t have helicopters, but what we did normally do is we would get the spray plane over to fly and over to kill the mosquitoes and the flies and that type of thing on the farm like kidding me. It was that while the guests were there, no we usually tried to do it in the morning before anybody showed up. Smarts, but you don’t, you know, you only got about eight or 12 hours, so like by later in the evening, the flies would be out, but they usually didn’t matter by then, that’s right.

Jay Whetter 12:58

You traveled around the world with Continental Grain, that’s correct. And I saw one story about some strange thing you ate in Italy.

Francois Labelle 13:08

Oh, ate all kinds of strange things, but you know what I’m getting? Yes, deep fried. Brains balls. Yeah,

Jay Whetter 13:17

no. Brains head balls.

Francois Labelle 13:22

What were they? Well, they were just little round, little, round balls of brain, a brain that were deep fried. And what animals brain, I really don’t know right now.

Jay Whetter 13:36

How were they were they were totally good, as long as he could deep fry anything and it might taste good.

Francois Labelle 13:41

No, you put enough breading and spice on just about anything, and it’s edible, isn’t it?

Jay Whetter 13:45

Why was that so noteworthy for you? Just because, because it was brains, or what was,

Francois Labelle 13:49

I think it got to be more noteworthy afterwards, when you started hearing about all the potential diseases and problems that that you had associated with, you know, the brains and the spinal and some of the, some of those, and the crazy things. Do

Jay Whetter 14:07

you think that’s the strangest thing you ever eat?

Francois Labelle 14:13

I’m not sure if I didn’t run across some other strange things. I can remember we had some little fish that were about two inches long and that they were all you could see whether there were two eyes too little. They were white. There were two little black eyes, and there was another little hole in the bottom, a little black hole on the bottom. And these things were extremely expensive, and they were only available for about a five to seven day period off the coast of Spain. And yeah, we were in Spain and had that as an appetizer one day for lunch. Not

Jay Whetter 14:47

not live No,

Francois Labelle 14:53

I would draw the line at that live fish, a live fish, or even live insects. At. People ate and so on. I did have a week rest one time from a group of Japanese people that were touring our facility. And we were cleaning lentils, actually, and there were a lot of sun, a lot of grasshoppers in there. And they were, they were wanting us to dry the grasshoppers and we could export them to Japan,

Jay Whetter 15:23

okay? I mean, there’s a lot of insects in cuisine around the world. So grasshoppers in Japan is a thing. Well,

Francois Labelle 15:31

I guess it was. They really want us to do that, but unfortunately, the way, you know, when you handle them, they end up in a bin and they heat real quickly. Yeah, right. So we weren’t going to touch that store them separately,

Jay Whetter 15:44

yeah? Well, it’d be interesting. I mean, that could be a side business for people in southern Saskatchewan and southwest Manitoba, where grasshoppers are a problem often, well,

Francois Labelle 15:53

some years, but some years, a lot of years, not hopefully, but grasshoppers have been a problem on years. So

Jay Whetter 16:02

you weren’t in Italy and Spain to eat brains and insects and little fish. What were you doing there?

Francois Labelle 16:10

Merchandising, actually at that time, was merchandising lentils,

Jay Whetter 16:14

lentils, and that was, I mean, we think of lentils and peas as a huge part of the prairie agriculture economy right now, but you were there kind of in the early days of both of those crops. What was that like, seeing that growth? Yeah, when,

Francois Labelle 16:30

when I started and first got involved in peas, like, I’d say there was like 85,000 acres of peas in Western Canada. And of about 60,000 of those acres were within probably an hour of Carmen, which was where my home base was at the time, but they quickly moved to Saskatchewan, because there was two pockets in Saskatchewan, and they were doing very well. And it was around the same time that we started having a disease issue in Manitoba that was killing off our peas. And we were able to grow or get 6070, bushel crops in Saskatchewan, and we’re getting 2025, Bucha crops in Manitoba. So they quickly disappeared. What was

Jay Whetter 17:19

the yield before that disease came in

Francois Labelle 17:25

the first years that I was in peas, like we were 35 or 40 bushels of peas was not unheard of. And actually peas were at that time, a lot of grew. A lot of growers found them to be mortgage savers. Was that right? Because they were, one of the few crops that you were able to to market without quota.

Toban Dyck 17:45

Okay, okay, outside of that, right? Yeah. And

Jay Whetter 17:49

this was when, exactly Francois, what year, or years 7980

Francois Labelle 17:52

is when I first started dealing with peas. And you’re

Jay Whetter 17:57

also dealing with lentils, right? Just, I’m gonna get the lentil acres. And then, yeah, so you’re 85 85,000 acres of peas, mostly in Manitoba. What was, where was, what was the lentil crop like, and where was it being grown? Lentils

Francois Labelle 18:09

at that time, were being grown in Saskatchewan. There were some in the basically, I’d say the first areas, and I don’t quote me on it, I could be wrong, but was mainly in the Regina Plains area. And you know, the drier area, they didn’t go that far north. They didn’t go into the darker soil zones up there and so on. The moisture was an issue. You know, growing them was it was, was an issue at start. And yeah, they, they started in that area, but, and

Jay Whetter 18:41

then same number of acres, or, I mean, 10s of 1000s, not much more than, Oh,

Francois Labelle 18:46

you know, I think 7879 I, you know, I don’t know if, I don’t know if there was 25,000 acres of lentils in Saskatchewan. Well, that’s changed so much. Yeah. Well, it changed a lot. You know, there was a lot of work done at market development and that type of thing. And, you know, we got into some, we got into good markets. And at that time, you know, I think a lot of people would say a good market was a market that would pay. And, you know, we were able to export a lot of those crops to Europe. Yeah. And there was a, you know, there’s big demand for the lentils over there.

Jay Whetter 19:25

So was Continental Grain a leader in this, like, can you go, Can you trace the growth of lentil and peas on the prairies to some of that work that Continental Grain was doing in 1979 1980

Francois Labelle 19:40

Continental Grain got involved more in the pulse crops in 85 when they bought cdex Canada Limited, that which is not the same company as cdex and litel, but it was they bought that the company, and that was their first start in peas in. Canada. But at that time, they already did own a P facility in Lewiston, Idaho, so

Toban Dyck 20:06

they had some experience. They had a little bit of experience. Yeah, and what was the hope like? Was there a lot of kind of, did see? Did a lot of people see potential in the pulse, kind of expansion in Western Canada? There

Francois Labelle 20:19

was, it took a while to catch on, but, you know, it was one of those things where, quite often, the grower would grow crop of lentils and or a crop of peas and get a good yield, yeah, and the neighbors would be looking, you know, they would be looking and seeing the benefits of it, and the growth potential, or the return to the farm. It’s

Toban Dyck 20:49

interesting, especially it’s interesting thinking about it in that lens of trying to grow a farmers wanting to grow a crop outside of that, that supply managed system to how that was probably a big incentive, like you mentioned,

Francois Labelle 21:03

that was that helped the growth in a big way. Because, you know, if a grower had a quarter section of peas, which would have been a large acres at the time, because most growers would probably have started with like, 40 acres or 50 acres type thing, right? But you were able to allocate those pea acres or those lentil acres to wheat, right? So if you had a four bushel COTA, all of a sudden, you might be able to sell, you know, another 200 bushels, if you had 50 acres. And you know that, that it was also at a time where, you know, we had poor movement, overall, poor movement of wheat and a lot of those years

Toban Dyck 21:45

was, was India a big was it an existing market for us? At that point,

Francois Labelle 21:50

India really became an existing market in about 8485 that’s just when we first started really getting there. Was a, there was a huge need in India at that time. They were, they were deficit in pulses. They had had crop problems. And that’s where we started exporting peas to India. One of the big things as well exporting at that time is, I think that was probably some of the start of shipping product in containers. Bank containers,

Jay Whetter 22:24

interesting, and what was the advantage for for containers, of containerization, of peas going into India,

Francois Labelle 22:32

a buyer in India didn’t need to buy a 5000 ton parcel. They could buy, you know, a couple 100 tons and get it shipped over to three month period. So it fit better into their their marketing over there as well, right

Jay Whetter 22:47

the so they mean the being able to seal a container and knowing that what you loaded here and on the prairies, and it was exactly what the buyer got in India. That wasn’t really the advantage at that time, it was more just the small lot sizes, the small

Francois Labelle 23:03

lot sizes, I’d say, you know, that that advantage of the buyer getting what, what they they they really wanted and so on, that was, I think, more of an issue in Europe at that time. You know, if they wanted a number one lentil with such a characteristic they could get it.

Jay Whetter 23:24

When you think of, you know, growing an industry within, within the prairies, like, was it people, or was it the market that drove this? Or was it, was it visionaries like you who saw the potential for pulses and helped bring it along. Or was that? Was it just the opportunity? Was there sitting in our laps, just waiting for us to grow the crops?

Francois Labelle 23:47

There were, I think it was multiple factors, you know, it was all of a sudden, you know, the increased interest in finding to diversify our crops, to get away from certain things, such as the quotas and so on. There was quickly realized the benefits of growing some of these crops as well and market potential. All of a sudden came along, really, the peas, the first peas that went that we started shipping out of, you know, even out of Manitoba. When those acres first came along were going to Cuba, you know, and going to the going to the Caribbean, you know, at the end of the Second World War, or during the Second World War, there was a all of a Sudden, pulses were not able to be shipped from India to places like Trinidad, which were a lot of East Indian people who settled there, and they weren’t able to get their pulses. So we started having some shipments out of Canada, and that was the. At the, probably the real start of the peas before that, the peas in Western Canada were basically grown in Manitoba, were grown for the soup industry, companies like the that we could remember, like Catelli, really could tell. You could tell, yeah, you know how that started. But then we, you know, we were some shipments of peas were going to Trinidad. And actually, the company that started seat X Canada, which was started for peas only, they started shipping peas there. And, you know, had a deal in Trinidad for receiving the peas, etc. And the Caribbean was getting pulses from Trinidad. And then eventually, in the late 70s, early 80s, it started. All of a sudden, Cuba was buying peas. And actually, those peas for Cuba were bought by export lab from from Russia and shipped to Cuba like Russia was the USSR was, was supporting Cuba. So we started shipping more and more peas there, and that, then that started, you know, we were shipping cargo ships. You know, small cargos, 710, 12, 15,000, tons of peas going to Cuba.

Jay Whetter 26:26

Well, its pulses are such a great rotation crop. Yes, with with an oil seed, or with cereals. I’m putting soybeans in the pulse.

Toban Dyck 26:39

You wouldn’t be the first

Jay Whetter 26:44

so, I mean, I think it would be, you know, good to have more pulse acres, but in terms of the market and the rotation, is it, are we at the right size now on the prairies for the pulse crop? Well,

Toban Dyck 27:02

that’s a that’s a big question.

Francois Labelle 27:06

That’s a big question. And, you know, it’s like, what developed the industry? A lot of factors. What will limit our acres, is a lot of factors. You know, how much you know from, let’s say, what’s happened in the last couple of months, political turmoil. What will that do to our markets, that type of thing? And, you know, I say last couple of months, but I think, I think we can go back further than that, like some of the problems in, you know, shipping or selling product to India, to China, yeah, and that type of thing. You know, they’ve become huge markets. I mean, pulses,

Jay Whetter 27:52

all of our crops in the prairies are highly dependent on exports. So is our livestock. But pulses in particular, I think almost all of them are exported. There’s not a huge domestic market. Well, the

Francois Labelle 28:08

domestic market that we’ve been able to develop more and more is, you know, the the value added market for the proteins, the proteins and so on. You know, the the rocket, the Rockettes and that type of thing. Yes, yeah,

Toban Dyck 28:24

right. Of course, I’m interested in, like, the, like, you’re probably kind of at the at the head of some of these. Like, what was it like to establish a new market for a crop? Like, when you’re traveling with continental and you’re visiting countries and like, Were you ever a part of that? Like, just suddenly there is a new customer that represents this amount of kind of business, or what export potential for Canadian farmers? Very curious about that.

Francois Labelle 28:57

I can honestly say in my, you know, my time with continental green, I wasn’t the one that would do that. Would help to do that, you know, probably more important was building our team within continental because, you know, we had, we had a tremendous office in Geneva that had contacts all over the world. So, you know, we were able to, you know, travel to travel to Geneva. We’d spend time in the office. We’d have meetings there, you know, share information and that type of thing. And then all of a sudden, maybe, you know, six months later, you’d get a call that Algeria wanted to buy lentils or and beans. You know, can you do something? And well, if somebody calls you and asks you if you can do something, you know what the answer is,

Jay Whetter 29:52

figure it out. Yes, yeah, exactly yes. And figure it out for sure. And was it? Was it a hard sell? I mean, Canada was. Not in that market. And they’re thinking, why would we buy lentils or peas from Canada? Isn’t that for that frozen place way up in the north? Yeah, what

Toban Dyck 30:07

do they know about? Well, it’s,

Francois Labelle 30:14

I think, like a lot of that was, you know, people would talk so Algeria would be looking for lentils. And Algeria was probably buying lentils before that, in smaller quantities from Europe. You know, I remember a buyer that we sold lentils to in Marseille, that his big business was shipping containers to Algeria. Well, when we sold, all of a sudden, when we sold, you know, 12,000 tons of bagged lentils to Algeria. That was a, you know, Algeria needed lentils. You know, they had social unrest. They had a drought. There’s nothing that will topple the government more than hunger, yeah, so, all of a sudden, they have to buy. So they’re, you know, they know that the lentils that they’re buying from, from Marseille, came from Canada. You know, somebody will make a phone call to somebody, right? You know, or somebody today would look at the internet and find out where the stuff’s coming from.

Jay Whetter 31:17

Pulses are unique, in a way, in that oil seeds are processed into oil. Wheat is ground into flour that people buy pulses exactly how they looked as they came off the field. What is that? What is the pulse market like in Algeria? What describe, for me, what that interaction with the consumer looks like. Yeah, I’m

Francois Labelle 31:43

gonna switch over to experiences I had in Greece and Italy. Sure. You know, I remember in Greece going walking through a marketplace, just, you know, a regular, very large marketplace. And saw the same thing in India as well, where, you know, the bag of lentils is there, and it’s open, and people can dip their hands in it and so on. And there’s a, there was an old broker that we dealt with in in in Greece that said to me, says, you know, people buy with their eyes, and they eat with their eyes, you know, it’s what they eat, is what they see, and they like so that they like this, you know, they like this quality. They don’t like that quality. And, you know, had the same, same thing happen in in Italy, we’re in a very large warehouse where there was, like, you know, 1000s of bags of lentils and peas and beans and that type of thing. And they, literally, people would show up, you know, two ladies would show up in a taxi, and they wanted to buy, you know, four bags of, two bags of lentils and two bags a piece. And literally, they would look at them, yes, we’ll take this one, we’d take that one type thing, and they would take, they would buy that. And they, you know, hand out the cash to the to Mario. And what’s it was, the guy’s name was Mario, okay, to Mario. And literally, literally, I picked up the bag and carried and threw it in the cab, in the trunk of the cab, and you were there for that, oh so valuable but, but you really saw how people interacted with that product. So

Jay Whetter 33:34

when you come back to Carmen and a farmer is is saying, Hey, why did you downgrade my black beans because, because they’re slightly purple, or they’re and you’re like, yeah, so you can just say, well, this is why, if they’re not perfectly black, we can’t pay you full price. Is Yeah. And then you tell this story, that’s,

Francois Labelle 33:55

that’s exactly the type of thing that we’d run across. And, you know, I’d probably the worst side of that is, I, you’d run across somebody said, I grew them, I harvest them. I don’t want to hear about it after that, you know, I just want my money and run. And that was one of the things that I’d say the pulse growers, you know, the three Prairie Pulse growers and as well as the Ontario bean dealers and that type of thing, really had to educate the grower to understand that that product was food. And, you know, yeah, yeah. You didn’t want to go buy us a rotten piece of beef. Did you Yeah? You know, right. Did you want to buy that’s a good analogy, yeah. Did you want to buy ugly looking beans or ugly looking lentils or ugly looking peas? No,

Toban Dyck 34:47

you know, yeah, but it would have marked a shift in how farmers think about their crops, right? Because they never had to consider that before

Francois Labelle 34:53

that exactly, you know, I think things like Warburton, right? You know, all of a sudden, you. Bringing back to the grower, the quality dealing with canners, on on the beans and so on. Like you know, some of the experiences we’ve had with the canners all of a sudden, when they start telling us their experiences of running across undetonated bombs in showing up in potatoes that were harvested in in Belgium. Oh, okay, literally, literally, and like, you know, having to shut down a factory and evacuate it and bring in a bomb squad, you know, something good boggles the mind, doesn’t it? Yeah, for sure. You know they run across that and why? You know how people, again, buy and eat with their eyes a can of beans. When you open the cut the can of beans and you see these little rolled up holes in the top of the can of beans. What’s it look like? Yeah,

Jay Whetter 36:06

right. They don’t like that, yeah, yeah. People, some

Francois Labelle 36:10

people would associate that with a maggot. Oh, okay,

Toban Dyck 36:14

right, right, yeah, spoilage or whatever. Yeah, that’s right. You

Francois Labelle 36:18

know this thing, but, but it’s, but it’s the hole that, once you get the whole wet, it rolls up, yeah, you know. So, you know, they do whatever they can to get away from that product, from that type of issue. So

Toban Dyck 36:32

that’s very fascinating, leaving. I want to

Jay Whetter 36:38

come back to one thing about peas and lentils. So

Toban Dyck 36:42

do it? Do it? Because I’m not actually leaving the topic, okay, but, but kind of,

Jay Whetter 36:47

well, I just want to come back to the disease in Manitoba that hurt the pea crop yield. You. There’s some thought that that might have been a phantomyces, so that it’s not, maybe as new an issue as as we think it

Francois Labelle 37:07

was. There was, it was never really, as far as I know, it was never really named and so on. But we had distinct issues with, you know, pea crops that were very healthy, and all of a sudden they were dead, you know, and or part of the field would be dead. And you know, that’s when we started growing seeing crops of peas come off at 12 and 15 bushels an acre. And you know, you’re competing with Saskatchewan. And even I remember, northern Alberta contracted peas in the mournville country, and Joe up there got 75 bushels an acre. So it’s really hard to compete with, you know, a $5 product at 12 bushels an acre, which is giving you 60 bucks, which compared to somebody that’s getting, you know, 75

Toban Dyck 37:58

Yeah, yeah. No, that’s wild. I was going to go with, take it to different, different place where you mentioned people buy with their eyes, and you’ve experienced that over and over again, which is, I think, I think a really interesting point in like, what you know part of this podcast is we talk, we talk about extension, and how you know the importance of taking innovations and research and extending it to a wider audience, and how that’s done. And I think the same is, is, is for, not only do people buy with their eyes, but they also learn with their eyes and like that, that tactile, you know, nature of you know, you know, Jay and I, you and I have talked about this, like, you know, what would it be like for a research presentation, to actually have physical props, right, to show, kind of what, what’s happening in a process, or kind of illustrate, illustrate their, their research findings. But in all of your experience, Francois, like, certainly, you’ve, you’ve, you’ve taken in all sorts in terms of kind of effective extension techniques or or habits or processes. What Are there any that kind of stand out to you as something that that you know we should as an industry, kind of lean in more

Francois Labelle 39:19

extension is so wide and varied. You know, I think when you when you talk about props and so on, well, we do that when we get people in the crops in the field, and we can show them the issues and the problems and, you know, some of the crop schools and that type of thing, they, you know, go to great lengths to show some of the some of the problems, and help people be able to identify them and so on. But thinking about extension, it’s not easy to you. It’s not a one case or one tool that will work for all, and it evolves with the time and that type of thing. You know, I was reading an article this morning, as you were saying that I do, I do have a bad habit of spending too much time reading sometimes. I

Toban Dyck 40:21

didn’t say it was a bad habit, but, well I did.

Francois Labelle 40:26

But reading, you know, looking at like 2025, coming with, you know, the decrease values of the crop and, you know, the tighter budgets and so on. Well, it may be easier to talk about people and how to save money, but it’s not that easy, because it’s going to be hard to get people to maybe drop some of the things that they’re doing, but if they could be shown that maybe some of the things that they’re doing are costing them money and not making them money, you know. So how do you get that Prop out, right? And I think, you know, we’ve been able to do that. And I think when you know you were at the pulse growers at the same time as I was, yeah, we could easily show this will return you x, or this is costing you x, right? And you know, things like, things like on Farm Research, but true research, not demonstration, but true research helps people to understand some of those things and so that they can take that and apply it. But then after that, what really one of the things that’s really required, I hate to say this, but the extensionists need to be able to sell it, and maybe they need to take a selling course. Sometimes, yeah, yeah. You know, like you take a selling course and they say, and you say, some, you know, you’re going to try to sell the tractor to somebody today, and the farmer is going to tell you, I’m not buying today? Yeah,

42:00

yeah.

Francois Labelle 42:01

Well, I gave you a clue. Yeah, he’s not buying today, right? But doesn’t mean that tomorrow he’s not going to be wanting to buy a tractor, but today, he’s got something else on his mind, right?

Jay Whetter 42:12

Extension, is marketing an idea, just like you’re marketing a product. That’s correct,

Francois Labelle 42:19

and people marketing products should probably understand extension fairly well as well, so that they can actually, they could probably do a lot better selling if they have good information and not biased. And yes, I’m an anti snake oil sales

42:37

person, that’s probably good company.

Jay Whetter 42:43

And it seems to be there’s more and more snake oil out there. Maybe that’s just we have. We’re blinded by the time we’re in. But, I mean, do you feel like there’s more product that maybe doesn’t have the Meritus rigor behind the you know, the preparation of the research into selling it. I

Francois Labelle 43:02

think when we look at at how beneficial some of the on Farm Research has been to show that some of these things, you know, I remember one of the first times I heard a presentation about a grower that said it was grower from Iowa that said that he, he did, did the research, did a non farm trial with, you know, that was replicated, etc. He did it proper. And then he had three years of data about this product that he was using, and it was not working. It was, you know, it was costing him money to use it. So the salesman came along the next year, you know, with his order book, ready to take his order, and he showed him the data, and he asked him, Why would I buy it? And he says, The salesman left, you know, so is it worth it or not? I and I know that some of these products will work some years and may work other years. They might work in some areas. They might work in some soil zones and might not work in other areas. You know, there might be a lot of application issues and so on. But at the end of the day, if it works, it works, and if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work, and if it doesn’t work, it’s costing you money. You’re

Jay Whetter 44:23

a proponent, then of on farm research are the associations, some of the commodity associations are, are pivoting to a focus on on Farm Research. You think that’s a good idea?

Francois Labelle 44:37

Well, I think I had an awful lot to do with the pulse growers getting involved in on Farm Research in a bigger way. And I think that answers that, yeah, if

Toban Dyck 44:46

you would have said no, I would have challenged about it.

Jay Whetter 44:52

I think that’s a really key extension related message. Rather than saying, don’t use these. Uh, products that might be snake oil trial, limited on farm trial. So how do you and that you made the point about three years, which I think is really important. But how does a farmer set up an on farm trial that that works and that gives reliable results?

Francois Labelle 45:20

It’s interesting. You know, now, when you look at just about every crop group across the prairies, and you know even some, and even from what I know in in Ontario, that the crop groups will work with growers to do on farm trials. And you know, if the grower has an idea, get hold the crop group and see if there’s interest in that type of thing. If they’re not, there are still private groups or private researchers that would help to develop a non farm trial, and, you know, collect data and that thing, obviously, those would probably be more expensive. But, you know, it’s something to weigh the benefits of that. But you know, that’s why I say demonstrations are basically of, you know, very zero, very limited value. You know, I remember I had a grower one time. Then he was growing, you know, he did a trial. He did a what, it wasn’t research, but a demonstration where he, he seeded half of his field, half of a quarter, one way, and he did something on the different on the other, the other the other half, so the other 80. But it was in the Red River Valley, where you’ve got a very pronounced slope from, you know, west down to east. And there was, it was a wet year, so the eastern half of that field was wet and had more standing water than the western side. And it was obvious, because you could see it through the summer. Well, that’s not,

Jay Whetter 47:01

that’s the trial was split north south, not east west. That’s correct, yeah, you

Francois Labelle 47:07

know things like that. So, you know the that’s why, you know a properly set up trial is so important.

Toban Dyck 47:15

And I’ve chatted with farmers who who’ve gone through that on farm, like some of these, on farm network kind of, I mean, on farm network is branded. That’s the mpsg. It’s on farm stuff. They really like it. Like they really It is that kind of, it hits home with them. Each person that I’ve talked to the importance of research, they see how it’s done. They see, kind of, the process, the protocols, the sensitivities, and then the data that comes out of it. I haven’t talked to anybody who hasn’t gained an appreciation for research as a whole after having completed one of those trials in their farm, which I think is incredibly valuable, right? Probably

Francois Labelle 47:53

the biggest thing is, as well as they’re able to live it every day. If they want to walk in that field every day, they can, you know, so they, there’s such an ownership, yeah,

Jay Whetter 48:06

of that, I just can’t help but thinking of the the woman, the home cook, buying lentils in the market in Greece. I mean, it’s almost like on Farm Research is, is like holding those lentils in your hand and seeing the value or not of a practice,

Francois Labelle 48:24

you know, yeah, same that that market in Greece that I went to there was also fish there. It was a large fish market as well. And, you know, you’d see the fish that they look at. And, you know, you’d, you’d see that fish that was starting to fall apart a little well, no one would buy it, right? You know, because would you buy a fish that’s half rotten? No, would you buy lentils that were half rotten? No,

Jay Whetter 48:50

yeah, I know. Would you buy a crop product that was not working? Not working?

Francois Labelle 49:00

It might not be as easily visual as looking at that bag or that fish or that piece of beef or so on. But, you know, if you have that three years of data, yeah, it might drive you to, you know, get the old gray matter working and making the decision.

Toban Dyck 49:18

What was it like I’m going to depart? Are you, yeah. What was it like starting or being a part of the process that started a crop group like Manitoba, Pulse and Soybean Growers.

Francois Labelle 49:33

You know, it was, it was interesting, because when I started the pulse growers, there was an there was a need. Again. We had an imbalance with government programs that were actually really, you know, favorite being favoritism to things like the wheat crops. It was a it was one of the stabilizing. Programs. Don’t ask me which one it was, but it was one of the stabilization programs, and then Ontario was able to get that program to cover their edible beans. But we had a budding industry in Manitoba for edible beans, and at that time, it was reg Stowe that was really pushing this, because he was well connected in Ontario, and he was one. He was developing the growers in Manitoba and so on. And there were others as a few others that were starting to grow beans, and, you know, so it started developing that way. So they really wanted to be part of that state of the stabilization. And then it grew from there, because Alberta was also growing some beans already. They had been growing beans under irrigation for years, and they wanted to be part of the program. So it started a need for that. So, you know, that built from there. And you know, not long after, well, you started seeing other things come along the line, you know, other other issues that needed attention and that type of thing, everything from transportation, you know, pesticide issues and that type of thing, and, you know, and just things started rolling. And there was more and more to do. And there was, you know, there was good people involved, and people that were very interested in seeing growth in the industry. And

Toban Dyck 51:28

so this reg, right red story, yeah, so were you? Were you, kind of, were you a part of those discussions? Then, when reg was reaching out to people in Manitoba, or, kind of, it

Francois Labelle 51:39

right from the beginning, there was a small group that got together and they wanted to form this, this association. So I, I got a call from the provincial government that said they were looking for industry representatives, and that’s how I ended up involved in it. And, you know, I don’t know it was it was interesting. It was interesting. It was interesting. It was an interesting growth issue. And, yeah, and you know, you could, you could sense the need for, yeah, another voice

Toban Dyck 52:12

that’s super it’s super interesting. So, Jay, you have a question again.

Jay Whetter 52:15

I was just gonna mean with, with a new crop, or relatively new crop is that, is that association essential? Like you look at associations that have been around for 50 years and and maybe they’re still essential, but is it? Is it that critical formation of an association at the growth stage, is that? Is that an essential step in your mind? I

Toban Dyck 52:39

mean, I guess, I guess one way to frame that question also is kind of, what, what did you see? How did that benefit pulses in Manitoba after that association was formed too, but yes, well,

Francois Labelle 52:51

you know, you start seeing gains fairly quickly on some of this, like, so, you know, the probably one of the first things that happened is like, you know, the government was willing to listen to the growers and but they didn’t want to listen to just one group. So since that, there was a difference between Ontario and Western Canada. You know, we ended up producing a forming an association called the Western pulse Growers Association, which was Manitoba and Alberta. Saskatchewan came in afterwards. But, you know, so they were able to get the government to to open up and and listen. And then they got, you know, stabilization part of the program, you know, covered for the for the the beans and that type of thing. And so it just grew from there, you know, and but you look at any of the you know, you you look at like when the lentil or the pea and lentil industry started growing in Saskatchewan, it was the same thing as, you know, you got to that grower group got together, and they had, they had support from from the research community and that type of thing. And they got support from the government to help the growth. And, you know, very quickly, you know, you’d get, all of a sudden, you’d get, you get a buyer coming to Western Canada, or coming to Manitoba or so on that wanted to to talk about the crop so quickly you could get a, you know, a grower or two together to talk to them about the crop. And, you know, because of the association it, it quite often was, it was almost like a magnet that would draw things to it. You know, it might be a problem the grower, a grower, group of growers, had, and it would come to the association, and it’s something that was addressed, and that type of thing just

Jay Whetter 54:45

just as we I don’t want to miss asking you this, but we’re getting near the end. But like, if a farmer, what is the value of a farmer for getting involved in boards? I mean, there’s always. Struggle to find enough interest among farmers, but like, how, what would you say to farmers who are wondering whether to get involved, and what the benefit might be? Yeah,

Toban Dyck 55:08

we understand that. We were just, you know, chatting beforehand, like, you’ve been on a lot of boards and, and you’ve sat in kind of various rooms and, and really kind of wanted to draw from that, that experience.

Francois Labelle 55:22

I think the the opportunity to broaden one’s horizon, and, you know, to broaden nationally and internationally, is a big, big issue, you know, and it depends where the interest of the individual is, you know, it could be, you know, if they’re interested in the international market, they can go and see, you know, and I’ve, I’ve talked to and you know directors over the years, and you know directors that got the opportunity to go, you know, to Thailand to talk about soya beans, could really bring home what the buyers really want, or what or understand what those markets want and that type of thing. So it’s an opportunity to continue to learn. That’s the biggest thing. It’s an opportunity to continue to learn. And the saddest part that that I’ve run across over the many years is when you’ve got somebody that’s, you know, seems to be landlocked, yeah, on their farm or their area or their province or their state or wherever. You want to say that, that you know the world is so huge, and there’s so much to learn and so much to experience beyond that, you know, their home place that I think that’s the opportunity to learn from a board and from other people and so on, is, you know, an old saying is, you got to learn something every day, Otherwise you’re moving backwards.

Toban Dyck 56:59

Yeah, yeah, and spoken by someone who, like yourself, I don’t think we’ll ever stop learning that’s that’s quite that’s quite incredible. When you look back in your experience, and you draw from all of that, and you, and you look at the ag industry today, and just kind of, you know, shed the fact that this is being recorded and all that. What do you want to say? What are your thoughts on its current state? What do you want to say to it?

Francois Labelle 57:29

You know, the biggest thing we’ve got in the industry is that it it changes. It forever changes. You know, I’ve seen highs and I’ve seen lows. We may be heading downward, but we will go back upwards. So I don’t think people should despair. You know, the old adage is that people have to eat. Is going to be true forever, you know, and there will always be a marketplace for for people to to market their crops and so on. Sometimes it will be more difficult than others, but there’s still, I think agriculture is still one of the most important and best places to be, you know, and especially that you know, you can spend time outdoors or indoors, and you can see the world, and, yeah, understand the world. I think agriculture is an exciting place to be, and it will continue to be.

Toban Dyck 58:36

Are you still involved in the industry, in any advisory boards for anyone?

Francois Labelle 58:41

No, I talked to a lot of people and still read to read a lot, but no, I have, I’ve not been involved in boards, yeah, sort of backed away.

Jay Whetter 58:51

Well, you’re the, the only member of the Manitoba miniature donkey Association.

Toban Dyck 59:01

Well, I don’t know if you’re Are you the are you the only member?

Francois Labelle 59:06

No, we don’t have a Manitoba miniature donkey Association, but there’s the Canadian donkey and mule Association.

Toban Dyck 59:16

Well, Francois, it’s been an absolute delight chatting with you. I’m going to share one last anecdote. When I had the opportunity to work with Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers, I was chatting to some farmers locally here about about it, and a guy named a grower named Peter Lowen. I chatted with him. He’s a Potato Potato grower. He said, If you ever have the chance to work with Francois LaBelle, you should not turn it down, so I took Peter’s advice, and I worked with Francois and and absolutely no regrets. So

Jay Whetter 59:47

what? When we asked you to be on the podcast, what? What did you think?

Francois Labelle 59:54

Unfortunately, I know Toban very well. Sorry. I thought it would be interesting, yeah, and not that it is, it’s, I hope you found it interesting as well. Definitely, definitely,

Jay Whetter 1:00:07

very interesting. Yeah, no, I really, I mean, I said it twice already, but I really like that. You know, connecting with our consumers in agriculture, keeping them top of mind. And this your story about the market in Greece and the market in Italy, where the people are holding our product in their hands and making a decision on, should I buy this and how much do I want to pay? And I think bringing it back to the consumers is so important.

Francois Labelle 1:00:36

Somebody’s got to pay for this product, you know. So, yes, that’s important. That’s that’s why it’s important to understand what General Mills wants and a note or, or what Richardson want in their in their canola or, you know, because they’re taking it to an end consumer. So it’s understanding that they need.

Toban Dyck 1:00:58

Thank you so much. Yeah, thanks. Principal, so that was a great conversation, but there’s something I gotta kind of I gotta address the elephant in the room as it were would be. You came back to this numerous times, his time in Greece, where the consumer had to touch and feel the lentils and how important that was for you. So get your hands out of my lens. I’ve known Francois for a long time. And like I, you know, so I could go on, you know, but

Jay Whetter 1:01:44

I just had a really strong visual, you know, of a market with these, like, big burlap sacks of of lentils and beans, all different colors. And this, like little person behind all these, and then this woman coming in, like feeling all or looking at the I just, it was just a really striking visual in my head, and I just, and it’s this notion where you’re connecting with your your consumer, yeah, and you’re so as you’re, you know, you’re visualizing how someone is going to interact with the with the grain, or the livestock you’re raising, how they’re going to see the cuts of meat, or how they’re going to see the end product, yeah, and I just, we don’t have that, that clear connection right from the combine to the end user, like we do with pulses, like, as it comes off the combine, and I said that in the podcast, yeah, as it comes off the combine, it’s exactly how this woman in Greece is interacting with your product. And I think it just brings home the the importance of quality and keeping your your customer in mind every step of the way.

Toban Dyck 1:02:59

Yeah, no, it’s true. I mean, I did, I did. I was struck with that. I’ve grown, I grew black beans one year. Great experience. And, yeah, you can help with your sample. Is really important, like, how it how it comes into the hopper, becomes very important, because ultimately, that’s how you’re selling it to to the buyer, like you, you know, Western Bean or, you know, whatever. That’s how they’re buying it. And then, like, if you see a seed with a bit of a blemish on it, I mean, that seed will be, stands out, well, it’ll be on someone’s plate, likely overseas, right? That same bean with that same blemish was on my field, right, will be, will travel around the world. And, yeah,

Jay Whetter 1:03:41

and a person trying to put a value on your beans based on how it looks in that bag, for

Toban Dyck 1:03:45

sure, for sure. I mean, you can, when you go to a super store, or wherever a grocery store, right? You see the bags of beans. I mean, that’s very little processing has happened, right? Like, very little has happened between the combine and that bagging process. It is fascinating. So, I

Jay Whetter 1:04:02

mean, for all of the things we talked about with Francois that, that message about keeping your consumer in mind and visualizing that woman in the market, in in the Mediterranean, yeah, that was my favorite part.

Toban Dyck 1:04:14

Well, when I think of, when I think of Francois, I just think of somebody who is, is full of stories, and is just so aware, acutely aware of almost every element of that, of the chain, like he’s been connected to almost that whole, that whole line, and it’s been, yeah, it’s very interesting. And sort of the stories he told, what was your favorite? Oh, man, you’re putting me. You’re putting me on the spot. I always like the, he may have told it to me a little bit differently, but the, you know, those, those big meals he would have at his at his small farm near near Carmen, and it would draw people from like all, all over the world, essentially all over all Canada, states, but, but it’s just it was, remember the first time. I heard it. It was really fascinating, because it’s just, you think of Carmen. You think of this area too. It’s like, it’s very insular and small, but it isn’t, you know, and yeah, or needn’t be all of

Jay Whetter 1:05:11

his donkeys. What his donkeys are. You gotta go? When I you gotta go to his farm? Think of Shrek. Yeah. No, I want to. I definitely want to go there and see all of his little, tiny,

Toban Dyck 1:05:19

oh, they miniature donkeys are just the best. There’s we always 36 inches high at J withers at the weather. We learned about withers so Jamie and I always leave his farm thinking, we need to get donkeys. Oh, yeah, yeah. These are just, they’re just sweet, affectionate, yeah. Anyway, it was a great chat setup. It’s time time to end this one. Thank

Jay Whetter 1:05:41

you to our episode sponsor, Manitoba, Pulse and Soybean Growers who are urging you to prepare for the upcoming growing season by checking out their latest fact sheets for growing field, pea, dry bean, soybean and even new crop introductions such as fava bean and Lupin.

Toban Dyck 1:05:57

These fact sheets provide important information for managing weeds, insects and diseases in all annual legume crops. Visit manitabhpaws.ca. To find them. This has been the extensionists. I’m Jay and I’m Toban, till next time.

Jay Whetter 1:06:16

This has been a burr forest group production. We also want to thank the people you don’t see we’re here.

Toban Dyck 1:06:21

We’re chatting away with our guests, but there’s tons of people who work behind the scenes to make this podcast happen. Ryan Sanchez, our director, Ashley Robinson, is the coordinator, and Abby wall is our producer and editor. You