Episode: 19

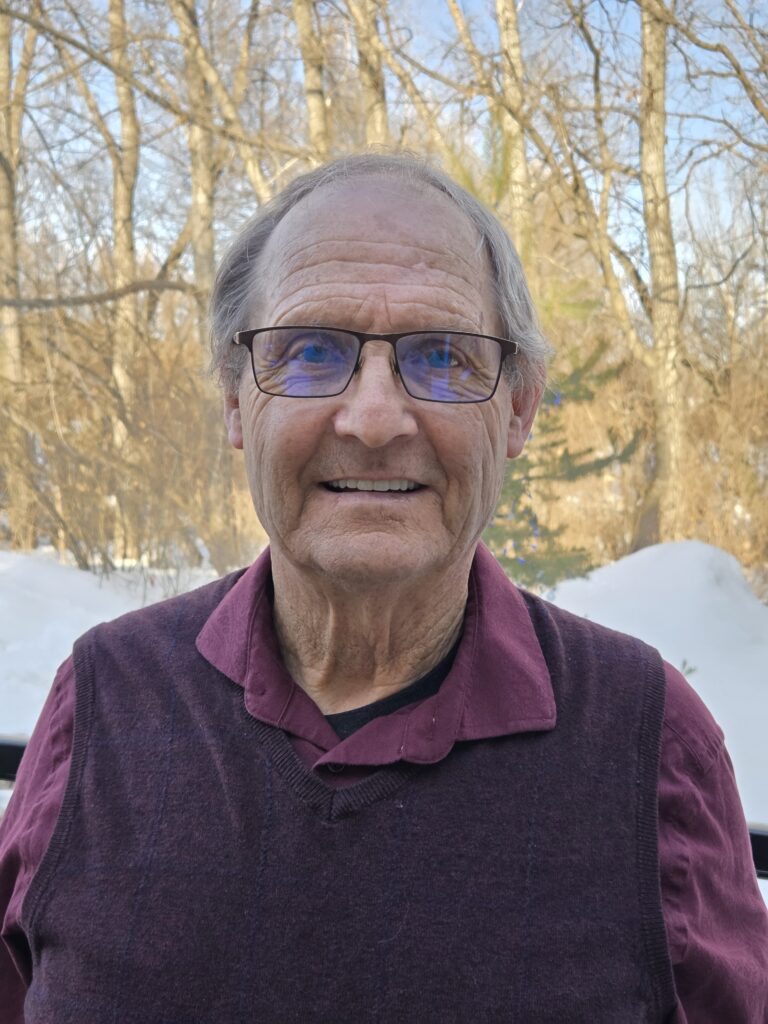

John Burns

John Burns found himself repeatedly using his chemistry background over his decades as a farmer. He approached every issue he faced on his farm like a scientist would. But what does that look like?

Listen here:

Transcript

Toban Dyck 00:00

Dyck. This is the extensionist conversations with great thinkers in agriculture. I’m Toban Dyck, and I’m Jay wetter.

00:16

Hey, Jay, hey, Toban. How you doing

Toban Dyck 00:19

good, good. So today, you know, today, I’m not going to be the I don’t need to be the token farmer,

Jay Whetter 00:25

right? We have a farmer as a guest. Today, we do have a farmer

Toban Dyck 00:29

as a guest today. I think that’s great. Well, it’s

Jay Whetter 00:32

good for us, as in the world of extension, to check in with farmers on messages that resonate and how they run their operations, and pull some little tidbits from from that side of the world. I mean, that’s our audience, but at the same time, it’s good to check in and see some of their business approaches and their communications tactics. It is interesting,

Toban Dyck 00:55

like you think of all the farmers throughout Canada, North America, world, whatever, and each of them kind of being their own. They’re, they are their own companies, right? They’re their own corporations now. And, like, it’s, it’s interesting. So it’s, I really, like, I draw value from learning how other other farms work, and especially when they’re, yeah, when they, when they, you know, and I’m sure, I’m sure this, this guest will be very, very similar, like they, they impart some insights, some some new things, and it’s always inspiring. I was like, oh, I should, I should do that in my operation. That would be, would really, really take things up a notch.

Jay Whetter 01:33

Yeah. So hopefully there’s a, I mean, two or three tidbits of the conversation that that people can take home and apply to their farm operations, or even just their organizational operations, because, like you said Toban, these are all businesses, or they’re run with a business mentality, and there’s a lot of crossover tips. Hey, one other thing we might talk about with John is hiking. Do you hike? Is that laughing? Yes.

Toban Dyck 02:04

Jane, you to ask me that question, yeah. Are you passionate? I do like I do like hiking. I do like hiking. Um, there was one hike in Manitoba that Jamie and I did last summer, summer before. It’s, it’s, it’s, forget what it’s called, right off the top of my head, right now, but, but it’s kind of billed as the, as the preparatory hike for the manatero Trail. Okay, so it’s by West Hawk Lake. Was it called anyway, it was, it was, it was, it took caught us off guard. It was quite insane. Oh, really like challenging. It was

Jay Whetter 02:38

challenging. Some elevation changes. Well, you’re in Winkler, which there isn’t even a hill level. Even a hill, let alone well that shouldn’t say there’s not even a one foot rise on your farm, let alone a hill.

02:50

We sense the air density changes when

Jay Whetter 02:55

you sit on the tailgate of your truck.

Toban Dyck 02:59

Hitting shield is just so high I just can’t

Jay Whetter 03:02

anyway. So have you done the mantario Trail? No, but I’d like to, yeah. I haven’t either. Maybe that’s an extensionist. Oh

Toban Dyck 03:10

my gosh, we should. We should do it. I think it’s a significant trail,

Jay Whetter 03:14

yeah, 60k or something. I know

Toban Dyck 03:16

a lot of people who’ve done it many times, colleague of ours, and if we’re naming names, so we’re not going to name his name, but is a runner, trail runner, I think he ran it. Oh, okay, he’s with a group of people who ran it. That would be quite that’d be quite something. I wouldn’t do that, but I would definitely hike it for sure. Yeah, definitely sprained my ankle if I ran it, none, for sure. All right, should we just not be able to finish? Did we get on with this conversation? Yeah, we should. But before we start today’s interview, we want to thank our episode sponsor Sask oilseeds.

Jay Whetter 03:56

Sask oil seeds texting service delivers agronomy resources event notices and urgent news right to your phone. Have questions, you can also initiate a two way conversation with the SAS oilseeds team. Visit SaaS canola.com/texting for details on how to subscribe. All right, welcome to the extensionists. I’m Jay. This is Toban, and our guest today is John Burns. And John is a farmer from Kandahar Saskatchewan. They he and his family run windy poplars farm, many trees, one farm. That’s what John just told me a few minutes ago. So welcome John. We’re going to talk about all kinds of things, from from chemistry and teaching to farming and branding, but just a first of all, welcome, thank you.

John Burns 04:50

It’s a pleasure to be here. We’re in such a fantastic industry, and we’ve got such a diversity of backgrounds and people, and I think that should be our story. Bank and not use it and not a

Jay Whetter 05:03

challenge, right? Exactly, and it’s, I mean, getting any farmer to agree is, is always a challenge, but, but we all have similar objectives in mind. Yeah, John, I want to ask you about your hometown. So I grew up in damned Manitoba, which is basically just a.on a map with nothing much left there except a few hearty souls. But Kandahar, interesting name that’s, that’s your your hometown, but not a lot going on there anymore, but it’s still meaningful for you. What does Kandahar mean to you?

John Burns 05:40

Well, it, it’s, it’s unique. It’s historically, it was renowned as being a, being a restaurant there called Sam’s place, and even John D for Baker had dropped in there and and people you hear you talk about Kandahar. Oh, is that? Is that steakhouse still there? But, but no, it’s now, if you’re driving on the highway, if you blink, you’ve missed it. But yeah, it’s real. Towns have have sort of eroded to a large degree, and especially those that don’t have a you know, industry that has been prompted by some entrepreneur so wing yard is actually our closest post office box location. We’re on the south shores, and I save the bigger quill lakes, notoriously water issues,

Toban Dyck 06:37

John, I gotta ask you, so I’m looking at you right now, and I could see you in your sweater. I see three. It looks like the periodic table of elements there. Yeah, talk, talk to us a little bit about that. Okay,

John Burns 06:49

so this is essentially the essence of where I come from. In fact, as I grew up on a farm, close to, actually where we we farm right now and but my wife didn’t marry a farmer. And and I was literally kicked off the farm as I as I was finishing my my high school education. I was, I was, I did well enough in in school, but I had six other siblings. My dad said, No, you could, you can take care of yourself. And so, and I enjoyed, you know, academics. So, so I and I, essentially, when I started university, I was thinking of mathematics, and because I like doing mathematics, but you know, as you as is a, I guess, a university education, it teaches you to get out there and find out what your passion is. And I went from math to physics, then I landed on chemistry because you you know things happen, and it’s you find there’s building blocks that explain the world, and so essentially, that’s what what chemistry is, I guess it’s meant for. In my lifetime, I enjoy teaching. I taught university classes for off campus classes in Saskatchewan for 25 years, as well as picking up, I guess, firstly, a hobby and then a bad habit and eventually turned into an enterprise, which we’ve reaped some rewards, because Essentially, that has allowed us to have 13 of our 16 grandchildren grow up within four and a half miles of where we live. And it doesn’t get much better than that.

Jay Whetter 08:50

No, John, John, you said your wife didn’t marry a farmer. So who did? What did she marry a teacher or a chemist or what were you

John Burns 08:57

I was still in university. I was I just started my doctoral degree. And and the idea wasn’t that, you know, in in the mid 60s, farming wasn’t necessarily a profession, is what you deferred to. And so, so, I think the thought was, if you could, if you make it somewhere else you know, not necessarily New York, you know, and you you’d survive. It would give you some choices. But, and that’s actually what, what I would advocate is education is probably the most important. It tells you, it molds you, tells you who you are. It gives you confidence, gives you choices.

Jay Whetter 09:44

And do you think when your dad kicked you off the farm, or whatever phrase that was he used, what did that I mean, he ultimately came back to farming, but I think you’ve incorporated that into your own family philosophy, where actually. Leaving the farm is an essential step in growing as a farmer. And is that, from your own experience, that where the reason you made that a farm philosophy or and what’s the point of that? Yes,

John Burns 10:12

because then farming is a choice, and then you’re not you’re committed to it. Farming is an enterprise that requires commitment. And if you’re always thinking, well, the grass is greener on the other side of the fence, or there’s other opportunities that you’ve missed, well, you’ve made that decision, and you’ve had that opportunity, and the other, I’d say, critical opportunity of having exposure to what’s what’s out there, so to speak, what’s, what’s, what’s in there, in the in the bigger world, is the networking. I mean, just knowing that you know you can approach others to help solve your problems, or, I would say your problems, they’re never problems, they’re challenges, they’re they’re things that you need to overcome and and so, so I think that’s that is critical. I think to at least, the way I feel an approach to farming could be, is to use all the resources and to and to make sure it’s, it’s, it’s the decision you’ve made and and get and and get committed to get, get, to get in the right frame of mind?

Toban Dyck 11:21

Yeah, no, I, sir, I certainly understand that. Like my, my my parents were the same way when I, when I thought about farming as a young child, they, you know, they, they definitely the requirement was that it had to be a passion, passion of mine, because if I wasn’t interested in it. So, John, I’m a farmer from Southern Manitoba, so you’re talking to us on our at our farm, my farm studio, that I shouldn’t do it if I’m not passionate about it, because it’s just not going to work otherwise, and and so that was always drilled into to me as well. Yeah. So just going to back to your your sweater. So just for the people who can’t, who are going to watch us on YouTube, and just, just going from it. So what, what’s on it is an F and then an a capital A, R, and then a capital M, lowercase n, all in three different blocks. So what, what do those mean? Well, of

John Burns 12:13

course, the those are part of the periodic table, so that’s fluorine, argon and manganese. But farming, farming? Is science.

Toban Dyck 12:28

Did you? Did you get that sweater made? Or did you find it somewhere?

John Burns 12:32

Actually, it was my son who actually found it on somewhere in the web. And it was a gift that, of course, I’m always, I’m always alluding to the periodic table and helping you how it understands, how we can understand our our world, you know. And I always, I will say preacher or suggest, think small, but then plan

Jay Whetter 12:59

big. I want to talk about your chemistry background and how that influences some of the decisions you make on the farm. Obviously, not all farmers have have a chemistry background. How does that play into, say, nutrient management decisions or soil health decisions, or anything else you decide it’s

John Burns 13:18

it’s actually the that’s part of the passion for me is that to help to understand and and essentially, I use the scientific method where you look at at what you know, what the issue may be. I’ll say, alluded to the problem. The challenge may be, look at the resources. And of course, soil is right up there at the top of our resources. People are very close, but soil is critical. So that’s the that’s sort of the starting point of, I guess, what we’ll call the ability to have a legacy and to make sure, once they make sure do the best we can so that it’s we have a future in agriculture. So we’ve we’re leaving, leaving the land, the industry in better shape than when we arrived. And I always find that working with living organisms, even though many we can’t see. And I and I guess that’s where, where chemistry comes in. We can’t see those atoms, but they’re pretty important. And so, same, same in the soil, you know, there’s microorganisms. So and trying to understand what it takes to make a healthy, healthy soil, a living, a living soil, because then it, it gives back.

Jay Whetter 14:46

So, John, what you’ve explained to me is what I could hear from any, any farmer. So I want, can you dig in a little on the chemistry side, like, what is, what is going on there, that, that you might know about, that the average. Farmer or anyone else in agriculture might not. And how does, how do we use that information? So ultimately,

John Burns 15:07

we’ll look at what might be something that we could change again, understanding living organisms and they need to be fed, and tweaking something we do. And one of the, you know, one of the big ones that is undeniable is the zero tillage, direct seeding, just the impact that that had, and now it’s having the, you know, so the technology to actually do more monitoring of changes, if we do even small changes, so ultimately, explaining what we can do and what we think is the best opportunity our farm to get a an improved, I guess, response from from from either its tenure, how we we do the agronomy, or have the the mechanics, to improve it, and then to log it, record it. So it’s that, it’s that, that scientific method where you you go through the the five steps, and then you go back and start all over again, so you’re never done. Nothing is so good that it can’t be improved, but you have to. For me, it’s imperative to understand on my farm what that step is, and not to, not to bring in too many variables. Farming has so many variables, and so to be able to manage those variables probably is would be a 14 forte that I would say we have had on our

Jay Whetter 16:45

farm. What are the five steps of the scientific method? So scientific

John Burns 16:50

method, though I like to follow, and I think it’s pretty universal, is that, first of all, you identify a problem or challenge or it may not be a problem, that that is even a threatening problem. It’s just an opportunity. And then we look at your resources, what you have around you that that help, that helps them you to address that problem, it could be people, because they all have knowledge, and we don’t want to always reinvent the wheel. Our soil is critical when we’re talking about agriculture. So those are a couple of top priorities. Then it’s the method. How are we going to go about planning and of course, follow through. And then comes the observations, making sure you you’ve dedicated enough time and resources to have, have have a follow through, to to to do the correct analysis, and then a conclusion. So what did we see? And in the conclusion, it can be something that that consent, that answers the problem you had, or the early or the challenge, or it’s still a conclusion, even if it, if it doesn’t, you look at the questions you have in that conclusion to then start to process all over again. So it’s not linear, it’s cyclical.

Jay Whetter 18:29

Can you walk me through an example of a decision you made on the farm that was driven by some of the scientific method experimentation that you had done.

John Burns 18:41

So I guess the back bit background here. So I farmed as a kid, you know, it was a lot of tillage going on, and we had a lot of black snow when I came back to farming. And, I mean, that’s a story itself. We I said, that’s not good enough. What can we do to minimize erosion? People have tried trees, etc, but in doing some research, we there was, you know, we were starting to get some tools, some chemicals, and one of those was glyphosate, that allows us to control weeds and keep the, you know, some cover on the land. And in our area, it was critical, because we have a very sloped land from in about a 12 mile range, we have an 800 foot elevation change. So you can imagine the water erosion that could happen and as well as the wind erosion. So that was the first thing I focused on, and attended a lot of meetings and read a lot of art. Tools. And so started using some chemical control of weeds, and did much less tillage. We didn’t have the the next step then, of course, was, then, how do we? How do we seed? What was the tool? So, so, but the very first one was, was, that was the focus, was not detail.

Toban Dyck 20:22

So yeah, you talk a little bit about, like, if there’s more to that previous story, for sure, continue. You talked a little bit about data over time, and how your farm records data, and how important that is for the development of your farm, which I agree with. And I think that’s really interesting. What I’ve struggled with, and this is just a selfish question, is, how do you how do you keep that data? Is it? Is it software, like, how do you over time? Is there? You’ve, you’ve, you’ve likely developed some good workflows in your in your farm system, and I’d love to chat a little bit about what’s worked for you? Well, initially

John Burns 21:01

it was one of the main reasons to be part of crop insurance, and even on the early stages of crop insurance, you could be part of a program where you actually identified all your inputs, and of course, you record the yields. So that’s tabulated in a in a very methodical method. So that was initial speech six years ago. We’ve gone more to a higher level, using climate Fieldview, where you know, sun could tell you what we did on what day and what chemical use and what the weather was like. So we’ve got a better ability to do benchmarking, to manage the variables and know what you know if something isn’t consistent, let’s look at more of the variables that may have had a factor and part of that then, though, we have to be to address those things that are most important to us, in the in the variable variability factors,

Toban Dyck 22:05

some of those, some of those programs have, kind of, one of the barriers to entry is just how much effort it takes to kind of input all your farm data and get and get going on these things that climate field view, and there’s, there’s a whole bunch of other ones, and I’ve been just, personally, I’ve been resistant to it, just because there’s that onboard, that onboarding process can seem a bit daunting at times. Would you say that it’s been worth it to have to have that kind of centralized platform? Yes,

John Burns 22:33

partly because I was doing it in my head before that that becomes more of a challenge. You know, trying to record what you know, what we did, what happened during the year. But I feel very fortunate in our operation. We have three engineers, we have a city planner, we have people who gravitate to that technology. And so it makes my life fun,

Toban Dyck 23:02

is a lot of it app driven, like, are you doing it on your smartphone throughout the day? Is that? Is that kind of No,

John Burns 23:07

mostly spreadsheets and we and just information challenging? And, of course, people say, what do you do in the wintertime? We plan, and if you plan, then the summer is fun, because then you’ve addressed the questions, you’ve got a plan A, a plan B, and ultimately you’re ready. Because we have a very short season.

Jay Whetter 23:32

Describe for me that planning process. I don’t want to, I don’t want to leave that because, because that, that I think is essential with a lot of farm management is taking the time in the winter to make a plan for the following year. What’s your process?

23:49

Oh, wow. Okay, what we’re

Toban Dyck 23:50

looking at, listeners is a fairly beautiful, actually, infographic. Or, I don’t even know what you what you would say, but chart,

Jay Whetter 24:02

so walk us through that. Okay, so

John Burns 24:05

as we’re harvesting, we’re already deciding what’s going to go in that next year, because you have to worry about residuals, how we can do the fall management. So I think crop planning and rotation happens several years before we actually put the crop in the ground. Partly the marketing, we will have marketed some of our crops even as much as two to three years in advance of actually seeding it just we’ll address why we do that another time, perhaps. But so, so, so in October, it actually starts and so, and that that’s and I’ll bring in something here that helps us. And I alluded to that we’re a team. We. So to be able to do all this single handedly would be very onerous and not nearly as much fun. And with with being a team, we use the strengths, and so it helps in the planning, and it allows us to to bounce things off each other, because there’s, again, a lot of factors that come into play, and you want to minimize being blindsided. And of course, that’s one reason we plan because then you know, you’ve we’ve got, if something changes, there’s no panic. We’ve got so, so even just the process of doing that is therapeutic,

Toban Dyck 25:46

like, like, yeah, I believe that.

John Burns 25:47

Because then you’ve, you know, we’ve got, we’ve got, we’ve addressed, what if, so canola drops $2 well, we lost two dogs. No, we didn’t, because we didn’t sell any you, you manage. So, so it’s just that mental, I guess mitigation of stress or and stress all stress isn’t bad, but it needs to be controlled stress. So that’s, that’s why we plan, and then that’s, and it, it works really well for us, because then we have our, like, right now, we have all our inputs in place. We have, you know, machinery set up. We we do our our machinery assessment is before the end of the year. What do we need? What do we need to repair? So this is, and then we have a shop so, and we have, we actually have, you know, eight full time employees. So that also also keeps us on track, too. So it’s not, it’s not a challenge. It makes us aware that there’s things to be done and we need to use all our resources. I

Jay Whetter 26:57

really, I want to, I don’t want to leave this planning thing. Hopefully you’re okay with that Toban for a bit, but for sure, I just think this, this process and then so you’ve got these spreadsheets of information. You’ve got your your two to three year planning ahead, which I do want to get to, because I’m really curious about what crops you’re marketing two to three years ahead. So yeah, so how could that look I just want to park that for a sec, but I just so do you set aside a weekend where everybody, all of your eight staff and your family, get together, and so who do you sit around a table with an agenda? And who’s there? Just describe for me how this, this, the actual planning event looks like,

John Burns 27:42

okay, I don’t know if you were on the website, but we have a boardroom, and we have what are called Monday morning meetings, and that’s Monday morning management meetings. So most Monday mornings, other than if we’re very actively farming. We still do have phones and and we can communicate, but we try, we make the best effort to have a Monday morning management meeting. And actually, prior to that management meeting, there will have been a all employee employer meeting for the week, that’s at eight o’clock in the morning. On Monday morning, there’d be a farm planning meeting at nine o’clock. From nine till noon, there’ll be a management meeting. So all the those that are in the management team, which include, there are five of us on that, that board, and so we will go through things that have come up and addressed and and we would have an agenda, and there would be items that need to be on that agenda, so we try and be organized. So that’s the the operation. And then in non pharmacies, on Thursday, we will have a day where we will bring up specific items that we want to, don’t want to do in management, that sort of agronomy, meeting with either the banker or inputs people or etc. So so that’s in, I’ll say, the off season. That’s the format. And we also have part of the bigger picture. Is we have family meetings, because this is a family farm, and we have four of those a year that include so two of our children are part of our farming. Children are part of the farming enterprise. Two are not. But all are part of the farm family. So opportunities, in fact, we have to return to farm members now, and they are from the not one of the non farming families. They have worked on the on the farm with the farm. They’ve both got degrees in agriculture, and they have worked off the farm for three years already, and they’re moving back. They’re coming back to be part of a farm operation, but they’re from one of the non farming families.

Jay Whetter 30:13

And why do you have the non farming family members part of that those quarterly meetings. Why is that important? This

John Burns 30:22

is a family farm, and it gives, does it, and we go out to all of the our grandchildren, our grandchildren, and on down the line to have the opportunity to work in agriculture, which is the best, okay, and most rewarding industry there is.

Jay Whetter 30:45

So it’s just to make sure everyone knows that there’s an opportunity there. So the two siblings, who are not farmers themselves, they’re there with your objective that maybe their grant, their kids, your grandkids. You want to make sure that they have that opportunity, even though their parents might not have been interested or found opportunities elsewhere that’s really interesting. Or,

Toban Dyck 31:07

or is it or as, and this is a question to everybody here, or is it because I get it, you know? Or is it an awareness thing, where there is a sense that even the the family members who aren’t involved in the farm, because it’s a family farm, are deserving of just knowing how this operation is going, whether or not they’re a part of it, they’re just kind of, they’re brought into that conversation is there also value in in that and not contingent on them, like that’s necessarily coming back to the farm, but it’s just, hey, you’re a part of this because You are a part of the family, we want to just keep you in the loop, yes and

John Burns 31:45

yes. So even to go beyond you know, secession is is critical to a farm legacy. So that necessitates that all of our children, or we hope, that they’re still friends after we’re we’re gone. You know that they understand what it takes and to avoid entitlement, because much it wasn’t our plan to acquire some valued assets, it happens, and it’s to put into perspective what those mean. And I keep at every, well, not every meeting, but most ladies, I say, and land is not a commodity,

Jay Whetter 32:29

right? This is really interesting. Yeah, land is not a commodity because

John Burns 32:33

in different people’s eyes, depending on their background, it has different values and different importance,

Jay Whetter 32:41

right, right? Yeah. That’s very Yeah. That’s very interesting extension. We often think of it as you know, livestock husbandry or crop management, but succession and human resources and family are obviously critical elements of a successful farm. Where did this? These this, this meeting structure, this planning structure come from? Is that from your own head and your own experience, John, or did you get some outside help in creating these structures?

John Burns 33:18

Well, I’d have to say that the the Bucha, Bud is probably in my head. But again, the only way to to, I guess, do due diligence, is to use all the resources that you have and and I’ll have to say, for many years till we knew that our our children were absolutely committed to farming. We didn’t formalize a lot of that transition. In fact, at that up till that time, you know, there wasn’t the land we could have been, you know, accused of child brutality if we passed on the farmer and insisted that they come to the farm. But all of a sudden, things have changed since about 2000 and so now we really saw the insight to be more proactive in, I guess, understanding, I guess, the value the opportunity and where every family member fits into that so because questions lead to fear, lead lead to misunderstandings, so we felt it was important to to, I guess, nip that in the butt. So we’ve probably been transitioning, and a transition isn’t just the assets, it’s, it’s the mentoring, it’s the the operation. What’s it’s the philosophy, you know, we we do scholarships, we value education. We anybody who wants to. Who undertake a course or learning program, whether it’s a university one or one that’s available. We help promote and assist that. So we commit, we commit dollars to that

Jay Whetter 35:12

you do scholarships within your own family, or is this for the community charity

John Burns 35:17

as well? And what the ones we do in the community are more for citizenship, you know, where they they they’re part of the community, and the community structure. Say, for once, for one thing, I’ll give one, one example of a young girl who’s in a 4h and and she raises a steer, and the profits that goes from that steer go to land bank.

Toban Dyck 35:43

Interesting. Would you say that your dad kicking you off the farm? Would you say that has inspired you to ensure your family has a place at your farm?

John Burns 35:55

The food bank, sorry, the food bank, not the land Yeah,

Jay Whetter 36:00

the food bank, the land bank. Oh, yeah, I’ve got

John Burns 36:03

too much history. Yeah. So I guess the reason I came back, or my wife and I came back to the farm, is I so I had my doctoral degree, and I was doing a postdoc in Kingston, Ontario at the time and had opportunity to work for the Department of National Defense or other chemical companies in central Canada. Can’t call them eastern Canada, central Canada, but I guess a part of the reason we came back is my mother passed away, or was quite sick early on in my Well, essentially from age 13 on, I saw very little of her, and when I was 16, she passed away, my grandfather raised, raised us essentially, and he was, he was starting to have health issues, so we decided to move back to Saskatchewan. The challenging part was the opportunities in 1975 to come back to to Saskatchewan, I took a high school employment opportunity for for a year, and then I worked for the regional College, some some doing GED, and some doing organizing programs. And then the next year, I was offered the opportunity to teach off campus university chemistry classes at Munster. The year after that, there was also opportunities at Parkland at Yorktown, so I and then I would do night classes at Belfort. So I was teaching university classes at three different locations and and at that time, farmers were struggling, and we just picked up a bit of land here there, because we could, and it was close. And so say, a hobby turned into, I guess, a bad habit after a while. But by time 2000 came around, I couldn’t do both, and we were sort of at 7000 acres, and that was kind of a startle. So I differed from from teaching actively at university, but I think still teaching, but in all that time, you know your the name of your program is, I guess, very appropriate or important to me, that the extension work, the ability to bring together the knowledge, to pass it on in a user friendly method to the farming community. And I say the farming community that also involves processors, and actually, to some degree, should involve consumers to understand how we can use this valuable resource, an important resource, and the stable part of Saskatchewan. So I attended as many programs extensions. I was on the ad board system for 25 years, and those opportunities were remarkable.

Toban Dyck 39:29

So in your in your world, in your experience with agricultural extension, vast experience, what, what methods have you found work really well. I mean, you come at this from a very kind of deep science perspective, where you have that you have that ability, how have you been able to extend some of the more kind of complex things, to to to an audience that may not know as much, may not have their PhDs?

John Burns 39:58

Well, the only thing. PhD does is it offers you the ability to network, probably more fully, and to, I guess, talk to people who are in in research from a perspective of practicality as well. So I guess that that was an opportunity, I think, for me, so one of the, the key things that I think that extension can do is offer support for on farm trials like early, early on so that, and I mean it means commitment, it’s sometimes awkward. Will they always be successful? No, but in the long term, it’s worth it’s a sort of short term pain, long term gain, when you do on farm trials and and so again, farming has more questions and answers more variables, so it helps to narrow. You know, being part of of access to extension opportunities helps to verbalize or or helps make a plan so that, and once you have a plan, well, then it’s easy to call through it’s confusion if you, if you don’t have the opportunity to talk to people who, who have dabbled, have committed, and I’ll refer to one fellow in particular that, unfortunately, he’s passed away, was Guy Lafond. I had a very close relationship with, with guy at the Indian Head research station, but he was a phenomenal person. Had phenomenal passion. And Saskatchewan, well, agriculture, Western Canada was a debt of gratitude.

Jay Whetter 41:52

Well, very interesting. Your net, you’ve mentioned the network a couple of times. You’re a networking who is in your network, who are essential people to have in network. So

John Burns 42:03

on our prior on our website is that we we partner with collaborative organizations, people we work with. You know, the machinery equipment suppliers, one of our most important and critical challenges on the farm is residue management. So we work with redekop and we test their, their their and pilot some of their, their, their equipment, their their choppers, yeah, and we were, my son worked for, initially flexible, and cnh, is it? And so he’s got connections there. We, we test, in fact, yeah, we test some of their equipment. They do trials. So seating, seating equipment, we would be into some think tank activities and more the the engineers, more than than myself, these days, where the individual companies are looking to what’s what’s going to happen in the future, what do they need to what types of equipment and and MacDonald was one we worked with for 30 years, the swathers we, you know, we work with marketing people, and We we we work with, with Cargill and their market sense program. We were one of the initial pilot people trying to think how long those but again, it was, it was probably 25 years ago. So again, the management end, so all the aspects that it takes. We could go into the financing, but that might get too many deals details of that, because there are some financial institutions that really do not understand farming,

Jay Whetter 44:14

just on the marketing. Because I had hoped to come back to this. So the timing is perfect. So you said you market some crops two to three years in advance. How does that work?

John Burns 44:24

Well, you can actually on the stock exchange. You can actually market wheat canola two years in advance. It’ll be a very thin trade, and it’ll be limited as to what you can do, but you can, but you can actually market, and we have, sometimes got as much as 10 to 20% of our grain market, even before we’ve well a year, a year, complete year. But we started, we start now for 2027, so we’re down there. The other collaborative race relationships we have is with things. With ingredients. I don’t I want to suggest we grow ingredients and not commodities. So we grow flax. So ultimately, it’s a relationship program that we deal with because it’s high omega three, yellow flax. And there’s a limited market, but, you know, the the schooler requires a commitment, not just one year, but seven years, so that, because they need to be in the marketing business for two to three to five to 10 years down the road, right? So we have, I won’t say, handshake agreements, but sort of commitments to each other where there’s good follow through that we will, we will grow for them, and we generally, our premium is sufficient to be significant. And so some of those we will will guarantee not just production, but there’ll be a price tag to it, because in that production commitment, there’ll be a

Toban Dyck 46:10

fixed price. That’s great. I We’re almost out of time, so I want to, I want to sneak a couple of things in here. One of them is your love of hiking, and I think that’s really interesting. And I think with the when your interview with, with with with Ashley, ahead of this, you talked about how you really enjoy hiking and that you you you treat these annual hiking trips as as almost spring training, you know, ahead of the growing season, which so I want to talk about the hiking, because I enjoy hiking as well. But I also really love the idea of, of kind of, of the idea of having a trip like that, or a season like that, where you are prepping your mind and your body for a busy growing season. And I think that’s a neat thing. I think that’s it’s a kind of a unique element to an annual kind of farmer’s schedule, where you take that time, because I know winters can be busy, like for for me and Jay and maybe you too. It’s lots of farm meetings and stuff like that. So there is that period of time when the when the conferences end, and there’s a bit of a kind of a kind of a lull between that and the girl when the growing season kicks off. And I love the idea of of doing something like that, you get the fresh air. You’re outside, you get to enjoy nature and your physical exercise. So yeah, talk a little bit about that. I think it’s great.

John Burns 47:30

So a rough rule of thumb is sort of mid February till like three weeks. My wife’s birthday is on February 17, and she says she wants to be hiking in the desert in shorts on February 17. So so we don’t go to the beach. We We have hiked the Grand Canyon seven times and kept it at the bottom the first four we packed everything down and back up with staying down there under two or three nights. The last couple times, we’ve sort of shared somewhere mode with with the mules, because you can, so we’re not taking because it’s and so it’s preparing, and I’m using the Grand Canyon as an example. So the elevation at the top of the Grand Canyon is 7200 feet. At the at the Colorado River, it’s it’s 2000 feet, where we live, at 2000 feet, just 1800 good elevation when you are having to exert yourself at 7000 feet climbing switchbacks, virtually vertically. Switchbacks at 7000 feet have to get conditioned before you can actually tackle that. So we actually go on hiking at about four to five to 6000 foot elevation in Arches National Park, or our canyon lands is our favorite. This year we hit the Capitol Reef. We have hiked it at Bryce or Zai and Zion. So those are, those are national parks in the United States. And much as there seems to be some, some, I won’t say, conflict, but some stress at the border. Once we get down there and we’re hiking, nobody, no nationalities. I mean, it’s just, it’s just just fun. But for me, I get in shape for spring, because we will generally, do, you know, essentially 2000 20,000 steps a day on average. So it’ll vary anywhere from from 10 to 40. But when we come back, having hiked at that elevation, and just before the busy season. I feel very invigorated, and plus my wife and I have had an opportunity to get together because she teaches piano and she gardens like crazy. So this is essentially the main main event for us to to kind of do stuff together without a lot of noise in the background.

Toban Dyck 50:24

I like that a lot.

John Burns 50:25

Yeah, and again, that’s part of 100 year plan. If I’m gonna hit 100 Year of

Jay Whetter 50:32

it, keep moving. So John, you’ve got a lot of philosophies to live by which I kind of like, and one of them is and maybe this, this planning, this hike, this preseason training, is an extension of this, this whole farm brand that you’ve created, you’ve got, you’ve actually got a slogan, which I wrote down so family, stewardship, community, innovation. Maybe that’s not a slogan, but, but that’s on your farm logo. You’ve got a website, you’ve got a video, and what is the motivation behind doing all of that?

John Burns 51:09

Well, again, if we’re talking about several generations and how people perceive us, there’s a danger and an advantage of having a website, people want to be a little bit judgmental, and maybe we, you know, you don’t want to come across as bragging, but yet we want to be transparent and what we value and so and we, you know, and it helps us keep on track too, that we we when you’re making decisions, if you use these, this, this vision, these vision statements, it keeps you on track to make as a group and generations, because we’re now, we’re actually into, we’ll be into the fourth generation here soon, because Our plan is, this is a legacy, that it’s not a 50 year old farm, it’s a 2000 year old farmer or more. So it helps everybody, I hope, to realize what our my wife, Linda and I, and my priorities are, and if we can carry that on, we feel that’s, that’s the best we can do to live forever. So we’re a little bit selfish, but it’s, yeah, it keeps it keeps us on track as a group,

Jay Whetter 52:39

right? So it’s for you internal as much, maybe even more so than any sort of external reach that a website might offer. It’s just to keep everyone on the farm grounded. This is our philosophy. This is our approach. So two kind of quick things, kind of stemming from that, I keep thinking back to your Monday morning three hour management meeting, and I can just see people saying, I don’t have time for that. But in some ways, maybe those that three focused hours just sets up for better profitability and productivity for all the rest of the hours spent in the week. Would you agree? Or what? Or having done it, do you think, well, maybe it isn’t the best use of our time. I think

John Burns 53:26

it’s critical to again when you’re dealing with so many variables. And so you can think, let’s say, either outside the box, or you’ll get consumed and get a tunnel vision. You get to sort things out as a as a plan, as opposed to a React. You know, it’s, you’re proactive instead of reactive. And I think in, I believe in agriculture, we have, we can get blindsided so many ways. So it allows for, say for good mental health as part of that. I mean, I don’t want to say that lightly or or a compound, either, but I really think that it helps us again. Excuse upon be grounded in many ways. We you have to again short term pain. Because sitting at those meetings, I’m thinking we could, we could be out there doing something else, but I think we do better outside the what we do when we’re not there. And so I don’t think it’s a it’s a handicap. I think it’s an advantage long term, and especially when you’ve got a group of people who have different talents, and you want to make sure they’re all their talents and their efforts are appreciated.

Jay Whetter 54:58

So I have, so the last thing I have is. Just, if you don’t mind, Toban. Just so what is your your message to your grandkids, and then that that next two generations removed when it comes to agriculture and your philosophy, your motivation, what message do you like to get across to them? I

John Burns 55:19

guess the first is have fun, if you’re not having fun and have passion. So right now, I would say for most, for our operation, but everyone you know, look for the opportunities in the challenges? There’s, there are always opportunities. You know, there’s, there’s books being written. You know that there’s actually more opportunity when there are challenges than when they’re not. It’s much like marketing grade when that’s volatile, even though it may hit a low that you don’t like. There’s opportunity to to take advantage of that. So that would, I think in agriculture, that’s what we have to look for. The glass the glasses is half full, not half empty. You have to have that, that mindset, and not just say, Well, we think of the future. No, it’s even more. It’s day to day, it’s hour to hour, it’s people to people. Look for look for the fun in every moment, because the journey should be enjoyable. Yeah,

Toban Dyck 56:26

that’s awesome. Well, John, it’s been an absolute pleasure chatting with you. I think both Jay and I could discuss it’s really fascinating, the the kind of the structures and the and all the all the kind of workflows and stuff you have on your farm and how you’ve been able to implement them. And I think, I think our listeners will be interested in that. I know I am as a farmer, we’re always looking for kind of more efficient ways of doing things, and how to at a better plan, and how to better, kind of navigate all this wildness of farming. So definitely appreciated your insights today, if

John Burns 56:59

I could just have a second. So if you look at the plant, so we essentially grow a variety of crops. And people say, Well, that’s a start. That’s a we, at times, have grown as many as 13 different crops, and and rotation is critical in our thinking for soil health. That you know, that’s something that’s, I think I would say forgotten, but people feel it’s an inconvenience, but we find it works for management. We we start harvesting earlier and we harvest later. That’s not always a a good thing from our spouse’s point of view, but we utilize our people, our equipment, more efficiently. I really believe the agronomy of that is right, because you’re not, you’re not always spraying at the same time. You’re not always harvesting at the same time. It throws the, you know, the parasites or the the you know, weeds or whatever, off balance. If we, if we change the routine, we keep them confused. So that’s, that’s, that’s part of it, so that that’s a management challenge, but it’s, it’s a management opportunity, and that’s one reason it requires a lot of planning as well.

Jay Whetter 58:15

Awesome. I appreciate that. Well, thanks, John. It’s great. Talking to you so much.

John Burns 58:20

Thanks for having me on and anytime.

Toban Dyck 58:33

Well, so that was interesting,

Jay Whetter 58:34

but I learned a lot about you know how to organize a business, and I think there’s some messages there that would be applicable everywhere, including that three hour Monday morning planning meeting.

Toban Dyck 58:45

So when I had my gray news column, I once had a column about how my wife, Jamie, and I would meet, I think it was like every Saturday morning, and we would discuss the farm. We would talk about like, you know, upcoming expenses. And that was primarily what it was this is always the big shocks of farming. Those numbers are always so high. But we found incredible value in just even though some of these conversations are really stressful, yeah, but just talking about them just kind of like so that we’re aware and that nobody is kind of, there’s nothing kind of being ignored.

Jay Whetter 59:19

And I think that mental health, because John mentioned mental health that, and you mentioned it too 100% where you just air airing of grievances or opportunities. Yeah,

Toban Dyck 59:29

the Festivus performing. But at least if you

Jay Whetter 59:32

get that out there, you get it off your chest. I mean, it might not necessarily change the the situation, that it might ease. Does it ease the stress a little bit? Yeah, it

Toban Dyck 59:44

did. And so I wrote about it, right? I turned that into six to 800 words. And actually, for on that column, in particular, a lot of larger farms in Manitoba contacted me and asked me about that. Meeting, because they were, you know, a lot of them even had employees, or they have more people operating on the farm than I do, and they were really curious about about it and how that works, and you know what the structure was like, because they want to do something similar, because they, I guess, probably a lot of farms to this day have, you know, there is an opportunity for things to get ignored and build over time, and so they want the idea of imposing structures in a way that that that helps, that helps kind of alleviate that, or mitigate that is very attractive to people. Imposing

Jay Whetter 1:00:36

structure. Yeah, it sounds heavy, but it’s also probably very effective,

Toban Dyck 1:00:44

yeah, and, I mean, the trick is to just keep that going, right? I mean, Jamie, we, we haven’t that. We haven’t been, you know, as committed to that as we should be. And, but there is value. There’s value in just returning, returning to it. Because, yeah, even though it’s uncomfortable at times, or even like my dad and I, you know, you know, setting up a structure there where, you know, maybe it is Monday mornings, we get together and we have a, we have a, you know, one hour, we drink tea and talk about the talk about the farm. I think that would be quite, quite valuable. And what I also like about it is that he is to have an agenda, because they have an agenda, and they treat it like a formal meeting, which I think even if it’s just my dad and I, or any other farm listening, if it’s just a two, two or three, maybe four people, you might think on agenda that’s just that’s overkill, but I think that’s really important.

Jay Whetter 1:01:31

I just keep thinking of flight of the Concords, when they had their band meetings, and the three of them were, yeah, the three of them are sitting around those little table, and then actually does a roll call. Brit present, yeah. Mary present, yeah. So,

1:01:53

yeah. Anyway, we’re laughing,

Jay Whetter 1:01:55

but it is, it is pretty important. Okay, so one last thing, and then we can sign up. So do you? Do you invite your siblings and your nieces and nephews to family meetings on a regular basis?

Toban Dyck 1:02:06

Like, like, how about never? Yeah,

Jay Whetter 1:02:09

exactly. And I think that’s I mean my family, I haven’t been to a farm fam farm planning meeting ever, but I’ve got two sons, and one of them probably would have been a great farmer. And I just thought, wow, that is, that is so interesting that you keep that greater family involved, knowing that maybe there’s someone out there who who could be the perfect next generation farm leader. Yeah,

Toban Dyck 1:02:36

yeah. No, that is, that is great. Yes. Great. Great conversation, once again. Thank you to our episode sponsor Sask oilseeds. Who want you to attend the Sask crop Commission’s field tour on June 25 at Davidson Saskatchewan, the tour will highlight 2025 on farm research trial protocols. Farmers and agronomists who want to attend can visit saskanola.com to register. This has

Jay Whetter 1:03:03

been the extensionists. I’m Jay wetter and I’m Toban Dyck till next time. This has been a burr forest group production. We also want to thank the people you don’t see. We’re

Toban Dyck 1:03:22

here. We’re chatting away with our guests, but there’s tons of people who work behind the scenes to make this podcast happen. Ryan Sanchez, our director, Ashley Robinson, is the coordinator, and Abby wall is our producer and editor.